Now for something completely different – JOHN LIDDIARD takes us round a Victorian steel-hulled sailing barque. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

WRECKS OF SAILING SHIPS generally tend to be more of archaeological interest than the wrecks of good steam- or diesel-powered ships. They have been down a long time, have been splattered against rocks, and typically wooden hulls have rotted away.

The Oregon is an exception. Although she was holed on a reef off Thurlestone in 1890, the 810-ton vessel was refloated and on her way to Plymouth before sinking in 30m. The steel hull has collapsed mostly flat to the seabed, but most of the structure of the wreck is still there and identifiable.

If you want to have a look at the wreck of a sailing ship in good condition, this is the one to dive.

Being small and fairly flat against the seabed, the Oregon is a difficult wreck to find. There are some small rocky reefs in the area that rise a metre or two from the seabed and can easily be confused with the Oregon on an echo-sounder.

Some of the guidebooks publish transits, but they are the sort of transit that is difficult to interpret until you are right on top of the wreck. Last time I went looking for the Oregon in a club boat using transits and listed co-ordinates, it took a good hour and a half of searching to find, and we were well away from the search buoy we had dropped.

Having gone to all that trouble, the position recorded in the GPS was overwritten by another trip before I got round to copying it to paper. So skipper Mike Rowley helped me out with some very precise numbers from mv Maureen’s differential GPS.

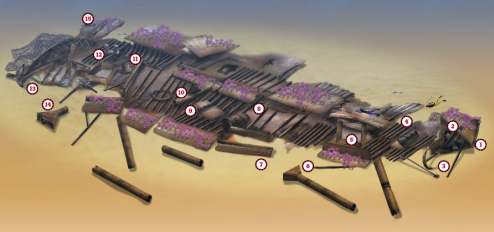

The bows and stern of the Oregon are the only parts that stand up far enough to give a really positive echo, so I will assume that the shot has been dropped on the bows (1).

The tip of the bows is intact and resting on its starboard side. At high water slack, the depth will be about 34m on the seabed and constant throughout the dive. Even when the tide is running, the current is not that strong and has not formed a scour.

The upper port side of the bows rises to 30m and is covered in a dense forest of hydroids, with some nice plumose anemones tucked under the edges. When the current is running a bit, a shoal of pollack forms tight above the bows, as ballan wrasse patrol individually closer to the wreck.

Inside the bows, the wooden decking has rotted away to leave the anchor hawse-pipes exposed (2). A large anchor (3) stands propped on one tip just above the bow. An unfortunate fisherman has lost his trawl-gear here, with an old trawl-beam pulled in tight beneath the anchor.

My guess is that this is much older than the nets that are caught against the upper corner of the bows.

The anchor-winch rests behind the bows (4), upright and attached to the steel reinforcing plate that would have secured it in the mostly wooden deck. The interesting thing about all the winches on the Oregon is that they are designed for muscle rather than engine power.

A little further back along the wreck, a steel hatch-surround from the forward hold is standing upright on one side with some hull-plates lying across it (5). This makes a small swim-through, usually with a shoal of pouting scattering out of your way as you enter.

Above the deck here lies the lower part of the first of the Oregon‘s three masts (6). Continuing back into the wreck, plates from the collapsed hull (7) are home to forests of really good gorgonian sea-fans.

Approximately amidships, a large steel cylinder (8) might have been a water tank. On a sail-powered ship I can’t imagine what else it would have been. Behind this is the shaft of a cargo-winch (9).

This is followed by a section of the main mast (10) and a steel ring that would have supported spars or sails on the mast.

Further back is the foot of the mizzen mast (11), upright in a deck-plate, and immediately behind this the surround from the aft-hold hatch (12), this time lying flat against the wreck.

From here the stern gains some structure, lying on its starboard side and rising 4m or so, as do the bows. Towards the rear of the stern the rudder-post, with steering gear still in place, is held just clear of the seabed (13). As at the bows, old fishing-net is draped across the back of the stern.

A few metres off the wreck above the stern is another mast-foot (14). I suspect this might have been the foot of the main mast (10), dislodged and shifted by some event in the Oregon’s past.

Following the line of the rudder-post through the stern towards the keel, the rudder (15) lies flat against the seabed.

With the wreck having fallen on its starboard side and collapsed, the other side of the wreckage is pretty much just hull-plates and keel, with further forests of gorgonians. In among this side of the wreckage are occasional ballast stones.

With the wreck being small enough to dive without accumulating much decompression, and also easy to navigate, it should not be too difficult to find your way back to the shot and ascend the line.

CALL YOURSELF A PILOT!

You might feel that Captain Albert Lowe had bad luck with the pilot allocated at Falmouth to bring him safely up-Channel. After all, he had managed, without a pilot, to bring his three-masted steel-hulled barque Oregon all the way from Iquique, Chile, round Cape Horn and across the Atlantic with a cargo of nitrate of soda, writes Kendall McDonald.

His orders were quite clear. He was to pick up a pilot once he reached Falmouth before continuing his voyage on to Newcastle. So aboard the 60m Oregon as she headed up-Channel there was a pilot, in addition to the 18 crew and their captain.

The trouble was, he wasn’t much of a pilot. In the dark and rain of the evening of 18 December, 1890, the Oregon managed to strike the Book Rocks, just off the beach near the dramatic arch of Thurlestone Rock in South Devon.

Captain Lowe immediately put his ship about, felt her come free and then headed out to sea. But she was badly holed and within minutes the captain had to order abandon ship. The first boat was swamped as soon as it was lowered, but the second launch was better and all got off safely. The Oregon sank minutes later.

No one, least of all the pilot, knew where they were. In the dark they drifted for 12 hours before spotting a light on shore, which led them into the shelter of the fishing village of Inner Hope, where newspaper reports say “they were treated with great kindness”.

The wreck of the Oregon was first dived by Kingston BSAC and was identified by the date of building – 1875 – cast into the boss of its wheel when it was built by Mounsey & Foster of Sunderland. Divers have recovered many of its lignum vitae rigging blocks.

TIDES: Slack water is two hours after high water and low water Plymouth. More experienced divers can dive throughout the tide on neaps.

GETTING THERE: From the M5 and A38, turn left on the A384 to Totnes and take the A381 to Kingsbridge and Salcombe. Hope Cove is a sharp right at Malborough village just before Salcombe, through very narrow country lanes. Just pray that you don’t meet a caravan coming the other way. For Dartmouth, leave the A381 at Halwell on the A3122. Maureen picks up from the floating jetty just into the one-way system.

HOW TO FIND IT: The co-ordinates from a differential GPS are 50 14.676N, 3 56.318W to 50 14.697N, 3 56.295W (degrees, minutes and decimals). The bows are to the south-west. Note that the GPS was set to display OSGB (chart) co-ordinates rather than the default WGS co-ordinates of the GPS system.

DIVING AND AIR: From Salcombe, Kara C, skipper Alan House. From Dartmouth, Maureen, skipper Mike Rowley.

LAUNCHING: At Salcombe the slip at Shadycombe car park is usable throughout the tide. Although expensive for a single weekend, this slip can be more economical over a week or two and is best suited to large RIBs. A slip at Hope Cove (Inner Hope) has a reasonable launch fee and is wet for just an hour or two either side of high tide. Below the slip is a firm sandy beach that is suitable for beach launching with a 4×4.

ACCOMMODATION: Liveaboard Maureen. Salcombe Information Centre

QUALIFICATIONS: Best-suited to sport divers and above. This is definitely not a dive for novices or just-qualified divers.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 1613, Eddystone Rocks to Berry Head. Ordnance Survey Map 202, Torbay and South Dartmoor Area. Dive South Devon, by Kendall McDonald. The Wrecker’s Guide to South Devon, Part 2, by Peter Mitchel.

PROS: An interesting chance to see the relatively complete, though not intact, remains of a sailing ship. It is small enough to be seen with a minimal amount of decompression stops, while at the same time big enough to make longer dives worthwhile.

CONS: Difficult to find.

Thanks to Mike Rowley and members of UBUC.

Appeared in Diver, September 2001